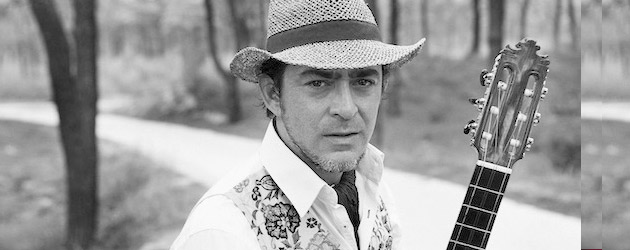

Interview: Rafael Manjavacas

This past year 2014, was the year of «Razón de Son», a creative new project of Raúl Rodríguez that was presented last summer at the Etnosur Festival, a work of flamenco fusion that draws from Andalusian, Caribbean and African influences, all developed with a new hybrid instrument created by Raúl himself, the «flamenco tres».

In fact, «Razón de Son» was chosen one of the best recordings of 2014 by critics and media, both national and international (Mondo Sonoro, El País, Rolling Stone, Aireflamenco, Rockdelux, World Music Central, Deflamenco, Planeta Jondo,… ). This year, 2015, after receiving numerous awards, the project is materializing in concerts and tours. Right now, Raúl is touring Andalusia: «and this is only the beginning, we hope that 'Razón de Son' will go far, and you have the chance to see it live and dance to it».

INTERVIEW

First and foremost, before getting into this new project, I have to ask you: What happened with Son de la Frontera?

You might say, generally speaking, we were out of synch, it was a group with several voices, and only if we're all in tune together and moving in the same direction, then it's a group.

You've been in the forefront, although not everyone may have noticed, in the world of music ever since Caraoscura, then with Kiko Veneno, with Martirio always, also with Son de la Frontera.

The first group I had was called Los Innombrables, a rock group, we did versions of the Velvet, of Jimi Hendrix, I played electric guitar and also sang. Then I discovered the flamenco guitar and Diego del Gastor, the music of Morón, I saw there was a way of playing that was very electric too, and that it was an important language to be worked via the flamenco guitar, and later on with the introduction of the tres in a flamenco way.

Every project you've gotten involved in has been like starting all over again.

That's how it's always been in my house, the tradition I know is one of creation, whether it's my mother, Veneno, Pata Negra…I grew up in an environment of people who quest and are always trying to learn something new. Along the way, you learn new ways of putting things together. New roads open up, sometimes because you're looking for them, and other times, spontaneously.

You've always had the role of musician in your various groups, with flamenco guitar and then also with the Cuban tres. When did you discover the tres, and what made you decide to incorporate it?

I'd heard Faustino Orama in several collaborations of «son cubano» and flamenco, with Jesús Cosano and many others. Around 1994, around the time they rediscovered the Buena Vista Social Club, I saw that the tres could work well in flamenco. Then in 1997 my mother, Martirio, went to Havana invited by Compay Segundo, and I asked her to bring me back a tres so I could start learning to play it. When I received the tres, instead of playing Cuban music, which I didn't know much about, I used it to play flamenco which was my thing, and I began to incorporate it.

Now we have a new instrument, a flamenco tres, made in Triana, and which combines flamenco guitar strings and lute strings, made by Andrés Domínguez, a guitar-maker from Triana, who used construction techniques of the flamenco guitar. An instrument which is half-way between two shores, while belonging to both.

Has anyone else done this as far as you know?

I had expected as much, but no, I've met people who've tried it, but there's very little. In Cuba they've played flamenco with the tres, but not here.

Another novelty about Razón de Son is that you play up front, and also sing.

Yes, I thought it was necessary, they're my own compositions, it didn't seem ethical to rent a singer, nor am I an actual singer or flamenco singer, I feel closer to being a sort of minstrel of the old kind, who tells stories in rhythm and music, and you understand what he's saying, we don't need a flamenco lament for this, it's more like a guitar-player's voice. In old times the same people who sang also played, with no pretense of being great interpreters, but seeking to communicate something. That's why I felt it was necessary to sing. It may be surprising, it's a different format, not flamenco singing, but not pop music either, somewhere in between, rather like the singer-composers and the way they sing in Latin America. Anyone wanting to situate things in just one definition is going to have a problem. The composer has to provide the vocals, in the old fiestas that's how it was, each one sang as best they could.

That's why one piece is titled «Si yo Supiera Cantar» ('if I knew how to sing').

Of course, I tried to make a song from my shortcomings, the idea of composition and creativity, that each one contributes his or her verse and music, no one has to be a virtuoso or a Pavarotti.

How did Razón de Son come about?

I think I was doing this all along, but I just didn't know it. I was studying anthropology in 1992, which is where the work begins. Back then I started to work with the first members of Mártires de Compás, then I went with Caraoscura, and from that point on I was doing both things, studying history and anthropology to discover what had gone on in our part of the world between Huelva and Cádiz, and the entwining of cultures and the encounter, studying the formation of the basic codes of our music.

I've always been a part of both places, everything I've done in music comes out of anthropological studies. At one time I thought of doing an anthropological study of the guitar-playing of Morón, in the end I never did, but the group came into being, with a sound of its own, ways of understanding the internal multi-cultural nature of the oldest pieces, with the incorporation of new instruments.

In this case, I wanted to do both parts, bring in the investigations already done… Faustino Núñez, Jesús Cosano, Santiago Auserón… and on the other hand, the creative and composing part, the collective wheel of creation, if we stop composing, the machine of popular creation might stop.

From that point on, I began to work on doing my own project, I had a phone call from Etnosur proposing that I do the production there, despite it just being in the early stages, they trusted me and the project, and it was fantastic they backed the initiative, coming from people who know so much about music.

Everything is based on music of more than 400 years ago, from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Exactly, it was important to know what was going on in those times, what there was before what we now know as flamenco. There was a multiethnic intercultural atmosphere, new products, different races living together in a very large territory, the Afro-Andalusian Caribbean, 500 years, Cadiz, Louisiana, Havana, Buenos Aires… And ships just kept coming and going, back and forth, theatrical companies, slavery… There was a basic contribution, little recognized, from Afro black music in all those ports, there were free men and slaves, both from abroad and local, in the 14th, 15th and up to the 19th centuries, people with a special gift for music, dance and singing. A population that had never been recognized, not in music nor in so many other things. Ten percent of the population was black at that time, slaves, free men, freed slaves, brown-skinned, black…it's been many hundreds of years to think we're so pure.

There was lots of music, basically the Zarabanda, the first black, Hispanic Andalusian dance, a provocative dance based on the 12-beat measure, with the guideline that came from the contact with those Andalusian ports. That's where I am, recreating that multicultural pluri-ethnic place, a very advanced place, similar to where our society is today.

I try to transport many of the codes from that moment in time to today's instrumentation, it's like making imaginary folklore, or imaginary proto-flamenco, creating from that point, 300 years of taverns with people coming and going, creating and interpreting dances that some people prohibited, imagine how provocative they must have seemed to them.

While it's not visually or formally flamenco, and there's no flamenco element, on the inside, what there is, are genetic codes of music which would later become flamenco.

The result is not only music, which is why the format isn't only a recording, it's also a book, and very complete.

I also needed to explain the reasons behind it all, looking for the way to create, starting to compose at the age of 40, it's a little late, but the attempt is new, innocent and honest, I'm searching for the reasons that set the stage for these sounds, I investigated in order to create, not to collect data.

Flamenco is a lot like an operating system for reinterpreting many things, and a very special ethic of popular and personal freedom taking off from whatever music surrounds us. In the formal sense, there's the concept of a type of flamenco with certain elements, history, mythology, industry…a complex system, but it's always a creative process and cannot be held back.

I think it's risky that today's singers refrain from creating their own verses, this could hold back the machine that keeps the course of tradition running. At the very least, it should be permitted to create within the traditional codes. People should be able to choose whether they interpret a classic repertoire, or propose new verses that pertain to their own reality, not the recreation of ancient problems that we probably don't even know anything about.

You've also tried to recuperate the dances of the era, at least in the presentation at Etnosur with the Kata Kanona.

They did a recreation of all those dances, a group of free-spirited women with no boundaries. My impression is that popular music has always been danced, in certain epochs it was slower, except for the danceable styles, but the rhythmic processes we have in flamenco can easily make those styles danceable, without the need to be a specialist in flamenco dance.

The zarabanda, the chacona, even the fandango, are genres that gave birth to many rhythms that are now only danced by trained dancers, you can find a basis for these dances to be interpreted by people without specific training in the rhythms of flamenco. On the other shore of Caribbean Afro-Andalusian, Venezuelan, Columbian, Cuban, Mexican music, there is a great deal with a 12-beat compás and rhythmic solutions for every level. In dance, the fusion of the tres is closely related to the origins of the Son Cubano, the instrument defines the genre, establishes the basic rhythmic units, readings of the rhythm of Afro-Cuban drums with the European Andalusian harmonic system. With the flamenco tres, what I aim to do is read the rhythmic portion of handclaps, dances and closings of flamenco, looking for the harmonies of flamenco.

The idea is that those forms have a global rhythm in order to be danceable so people dance to our music, an indispensable element for the survival of any music, if we can't get people to get up and dance, we'll be depending excessively on upper-middle-class theater-goers who are willing to pay to listen to music in a theater, sitting in a seat. Nowadays, this is very difficult, we need to get people dancing to those rhythms. And we the musicians can then play those rhythms with a lighter emotional load, making it more easy-listening.

What's the live performance format of Razón de Son?

My group includes drums, percussion, bass, a flamenco guitar and myself on the tres. Alex Tobías, Guillen Aguilar, Pablo Martin II and Mario Más. That's the basic quintet we want to work with. The songs can be adapted to different formats: myself alone with percussion, with a guitar, in trio format, with drums and bass or even as we did in Etnosur, the tres with an army of drums, collective music.

TOUR OF ANDALUSIA. Dates:

Cádiz, 6 February 2015

La Central Lechera (Plaza de Argüelles sn, 11004 Cádiz)

Concert: 9:00pm

Tickets: http://www.tickTickets.com , box-office Teatro Falla y el 902 750 754

Granada, 7 February 2015

Boogaclub (c/ Santa Bárbara, 3, 18001 Granada)

Concert: 11:00pm

Tickets: http://entradium.com Gran Vía Discos y Subterránea Comics

Sevilla, 12 February 2015

La Sala (Plaza del Pumarejo sn, 41003 Sevilla)

Concert: 10:00pm

Tickets: http://entradium.com , Record Sevilla y Totem Tanz

Málaga, 13 February 2015

La Cochera Cabaret (Avenida de los Guindos, 19, 29004 Málaga)

Concert: 10:30pm

Tickets: http://entradium.com , Discos Candilejas y La Cochera Cabaret

Morón de la Frontera, 14 February 2015

Teatro Oriente (c/ Nueva, 15, 41530 Morón de la Frontera (Sevilla)

Concert: 9:00pm

Tickets: Bar Pavía, Bar Retamares, Bar Casa Paca, Casa de la Cultura